Walter worked closely with USIA's first directors -- several of whom he admired, one of whom he did not.

First, Ted Streibert. I always think that Ted Streibert was a very good man to start the U.S. Information Agency, for various reasons. One of them I would like to stress here is that when USIA was created, the overwhelming part of USIA was the Voice of America. Only eight years had passed since the end of the war in which the Department of State was able to establish information programs in the different countries of the world. Let’s take France, for instance. It was a very small program. The budget for the Voice of America was the overwhelming part of the budget of USIA. There was one other very large area of USIA, where programs were really very developed, and that was in the occupied areas: Germany, Austria and Japan.

First, Ted Streibert. I always think that Ted Streibert was a very good man to start the U.S. Information Agency, for various reasons. One of them I would like to stress here is that when USIA was created, the overwhelming part of USIA was the Voice of America. Only eight years had passed since the end of the war in which the Department of State was able to establish information programs in the different countries of the world. Let’s take France, for instance. It was a very small program. The budget for the Voice of America was the overwhelming part of the budget of USIA. There was one other very large area of USIA, where programs were really very developed, and that was in the occupied areas: Germany, Austria and Japan.

|

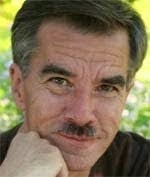

| Theodore C. Streibert, USIA Director 1953-57 |

So when Eisenhower appointed Streibert, who was a station

manager of a radio station in New Jersey, if I remember correctly, and a good

administrator, I had the feeling that the President did the right thing. I personally got along famously with

Streibert. We became friends, and

stayed friends after he left. May

I tell an anecdote? One day I sat

in my office, and Streibert called me, and he said: “Walter, can you arrange

for me to see the Pope next week?”

I said: “What?” And he had a slightly Brooklyn accent

and said: “You hurd me.” And I was absolutely flabbergasted. That was something that I had never

been connected with. So finally I

got up and went down to his office, went in there and I said: “Ted, why in the world would you want

to see the Pope?” He said to me: “Walter, you don’t understand. He’s in the anti-communist business;

I’m in the anti-communist business.

Don’t you think he and I should talk?” That was Ted Streibert. He was a very good witness before the appropriations

committees; we did quite well under Streibert. But he wanted to stay only one term.

So then, for reasons which I often thought about a great

deal and never quite understood, the President appointed the Under Secretary

for Labor, a lawyer, with the name of Arthur Larson. And he was a disaster.

And it was all due to one stupid speech that he gave in Hawaii, in which he called the New Deal “an importation from socialist Europe.” And that annoyed Lyndon Johnson very

much, who at that time was the chairman of the subcommittee that handled USIA

appropriations. I was at that

hearing. There was only blood on

the floor. We lost 25 % of our

budget.

|

| Arthur Larson in ABC Interview with Mike Wallace, 1958 |

Now, I happened to have been in a carpool, with the

Assistant Secretary of State for public affairs, a former high official of

USIA, the third ranking official, who had gone to the meetings with the

Russians in Geneva as USIA policy representative, obviously made a very good

impression on John Foster Dulles and John Foster Dulles one day asked him to be

Assistant Secretary for Public Affairs.

His name was Andy Berding, and I told him about this disastrous

appropriations committee hearing, and obviously Andy told John Foster Dulles. And John Foster Dulles for various

other reasons already had some doubts about Arthur Larson. And the story goes that he asked for his car for an immediate

appointment with the President, and went to the President and said: “Mr. President, we need another USIA

director.” And again,

according to what I’ve heard, Eisenhower did not object. In view of the history that says that

John Foster Dulles was utterly disinterested in information and cultural

programs, he took a great interest in leadership of USIA and he selected in his

own mind one of the top Foreign Service officers, a man with the rank of career

ambassador, George Allen.

And he asked George whether he wanted to be USIA director, and George

said yes.

|

| George V. Allen, USIA Director, 1957-60 |

George was brought back for a meeting with the President,

the meeting went well, and George Allen was appointed USIA director in

1957. As I look back upon all USIA

directors – and I knew them all – George Allen is at the very top. One of the finest minds, fully aware of what this was all

about and I can again tell an anecdote which indicates how his thinking

developed.

As you know, the USIA, when it was created, contained only

more or less information programs.

The cultural programs, and by this I mean really only the exchange

program, which Senator Fulbright sponsored and had so much faith in. When the USIA was created, Fulbright

put his foot down and he said “Well, that’s going to be a propaganda agency. I don’t want the exchange program to be

there.” And he insisted that

the exchange program stay in the Department of State, which it did. But sometime in 1958, after George had

been USIA director for a year or so, he wrote a memorandum to Loy Henderson,

who was then the Under Secretary for Management in the Department, suggesting

that CU -- Cultural Affairs from the State Department -- be transferred to

USIA. Henderson was very taken

aback and asked George to go to lunch with him. George Allen took me along, so I’m a first witness to that

conversation.

Loy Henderson started the meeting, to the best of my

recollection, by saying “You know, in 1953, when USIA was created, we sent a

memorandum to all top ambassadors and asked whether the split between

information and culture made any sense, and what our position should be. And you sent back a telegram saying

that’s a very good idea to separate the two. And now you want to reunite it? What happened?

|

| Livy Merchant |