Since returning from my last Foreign Service assignment in

Paris, I have been tackling some of the unfinished business I left behind at

the end of my stint as Public Diplomacy Fellow at George Washington

University.

Some of my earlier blog entries chronicled the 2009 “Face-off

to Facebook” conference at GWU commemorating the 50th anniversary of

the American Exhibition at Sokolniki Park and the Nixon-Khrushchev “Kitchen

Debate.” The exhibition was a landmark event in

the history of U.S. public diplomacy.

Sometime after the conference, I received a package from a gentleman

I had only met once, years before.

He had heard about the “Face-off to Facebook” conference and wanted to

share his own recollections of the Sokolniki exposition. A former Foreign Service officer,

John McVickar had served in India, Hong Kong, Bolivia, Washington -- and in the

U.S.S.R., from 1959-61.

In my

mind, McVickar was associated with a completely different historical episode.

It was at a New Years eve party in Stowe,

Vermont, that he had described for me what he believed was the most consequential

incident of his life. It was the

story of his encounter in Moscow in 1959 with Lee Harvey Oswald, a troubled

young man who had come to the U.S. Embassy in order to renounce his U.S.

citizenship.

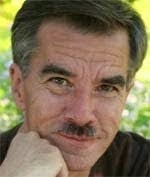

|

| John A. McVickar |

What I recall most vividly from that conversation was the

evident discomfort and frustration that McVickar still felt, forty years later,

about what his accidental interplay with Oswald had represented for the rest of

his Foreign Service career. He and

his boss, U.S. Consul Dick Snyder (who had conducted the meeting with Oswald), were only

guilty of having done what they had been trained to do under such

circumstances: namely to play for

time so an emotionally distraught American would have the chance to rethink

giving up his or her U.S. passport.

All the more so in this case, McVickar explained, since the young man had

arrived at the Embassy and announced his plans to become a Soviet citizen on a Saturday

when the Consular Section was officially closed.

|

| McVickar (l) and Dick Snyder at Embassy Moscow |

As it happened, Oswald only returned to the Embassy two

years later. In the interim, he had

been given permission by Soviet authorities to reside in Minsk, where he married a young, pretty pharmacist named Marina Prusakova. They had a daughter, but by 1962,

Oswald had had enough.

Disillusioned by his sojourn in the ostensible workers’ paradise, Oswald

was almost contrite in asking Snyder to return his passport so he could return

home. And it was McVickar who issued the visa to Marina Oswald that would enable her accompany her husband to Texas. The rest, as they say, is history – the

dark, tragic and still painful national tragedy of the Kennedy assassination.

By McVickar’s account, he was never able to free himself

from the shadow his role in facilitating Oswald’s return to

the U.S. cast over his career. He was interviewed by the Warren Commission, and his name is often cited in JFK assassination histories,

sometimes in entirely implausible ways.

In 1968, McVickar was “selected out” of the Foreign Service; only a

decade later was he able to secure his pension. It was not only the Oswald connection that complicated his career. A lifelong bachelor,

McVickar claimed he was repeatedly investigated by diplomatic security agents during

an era when homosexuality was viewed as a major vulnerability exploitable by

hostile intelligence services.

Although the allegations were false, McVickar told me, he did feel he

was guilty of being, in his words, “too friendly with married ladies” even if

he never allowed these relationships to develop into “physical affairs.” It was another era, to put it mildly.

When I met McVickar, he was practicing law in Vermont, in his

own storefront private practice. He

made it clear that he felt things had turned out differently than he had dreamed

they would as a young Foreign Service officer – and there was a certain

bitterness still in that observation.

And yet, I later learned, it was McVickar who founded and served as the first president of the Stowe Land Trust in the nineteen eighties and nineties – an

organization that has grown and prospered, successfully preserving many private

farms and woodlands from the developer’s bulldozer. That alone, it seems to me, is an admirable legacy.

John McVickar passed away in 2011, before I had a chance to

tell a little bit of his story in this blog. I am trying to redress that lacuna today.

No comments:

Post a Comment